Sexual pleasure after sexual trauma

“Pleasure is a feeling of happy satisfaction and enjoyment. Activism consists of efforts to promote, impede, or direct social, political, economic, or environmental reform or stasis with the desire to make improvements in society. Pleasure activism is the work we do to reclaim our whole, happy, and satisfiable selves from the impacts, delusions, and limitations of oppression and/or supremacy.”

Content preview: sexual trauma.

In the English legend of Robin Hood, Robin and his merry band of thieves famously ‘steal from the rich to give to the poor.’ But before the actions of the “outlaws,” the in-charge-of-the-laws of the story enriched themselves through excessive and unjust feudal policies, through exploitation and abuse of power. So Robin and company were not so much stealing as reclaiming what should, in a fair and just society, belong to all.

Trauma, particularly the trauma of sexual and gender-based violence (GBV), also relies on abuse of power, manipulation, and exploitation. It is also a relentless thief. What does trauma tend to steal? It frequently targets your sense of safety, your ability to trust, and your view of the world. It might steal your view of yourself, your psychological and emotional well-being, or your concentration and focus. It takes your time (so much time) as well as all the things you could have spent your time on if it hadn’t occurred. It often goes after your sense of autonomy, your relationship with your body, and your relationship with sexuality, including the ability to experience sexual pleasure even within the boundaries of a safe, informed, and enthusiastically consented to sexual experience.

What does healing from trauma look like? While trauma generally needs to be processed, one important aspect is reclaiming what, in a fair and just society, is your right to have: your right to safety (or safe-enoughness), your right to be able to form relationships of trust, your right to a wise and compassionate relationship with your internal psychological processes, your right to your body belonging to you, feeling good for you, and being able to feel good with others when you so choose.

While all of these aspects deserve time and attention (and patience and compassion, as healing is not a linear path or something that will look the same for all people), we wanted to offer some thoughts today on sexual pleasure after trauma, particularly as this can often feel taboo to discuss.

A couple of thoughts to before we get into specific strategies:

- While rape is categorically not sex, rape and sexual assault/harassment/GBV can make sexual encounters/sensations triggering for people, meaning that components of the trauma memory from the past can get associated with experiences in the present, thus activating the trauma response. If this happens to you, it does not mean that you are doing something wrong, and if a partner is present, it does not mean the partner is doing something wrong. It does mean there is work to do (and the nice part is, this work can be pleasurable).

- Pleasure, the feeling of enjoyment, is integral to healing from trauma. While desensitizing or numbing oneself to the pain of the trauma is a survival strategy many people need to employ at various times, it is not the same as healing from trauma. Healing involves the work of the survivor to actively integrate back to an ability to feel good, to experience a sense of aliveness and enjoyment. Sexual pleasure is not the only way to feel alive, by any means, but it is an important one for many people to reclaim. The following list suggests some ways to go about your process of reclaiming.

Sexual pleasure by yourself

Self-sexual pleasure can be a good way to explore your sexual preferences and to learn what you like and don’t like, and about what you want to explore with others and what you want to explore by yourself. It can also re-open pathways to a clear connection with the ownership you have over your body, your mind, and your sexual pleasure. You can experiment using toys (there is a ton of variety out there ranging from penetrative toys to externally stimulating) or by using your hands. Use lube However you experiment, we recommend using lube (i.e. personal lubricant). Lube can decrease friction and increase sensation, leading to more pleasurable experiences. You can always stop by the Office of Health Promotions and Well-Being office at the O’Connor Center to get some free lube; you can also ask at the university’s primary care clinics.

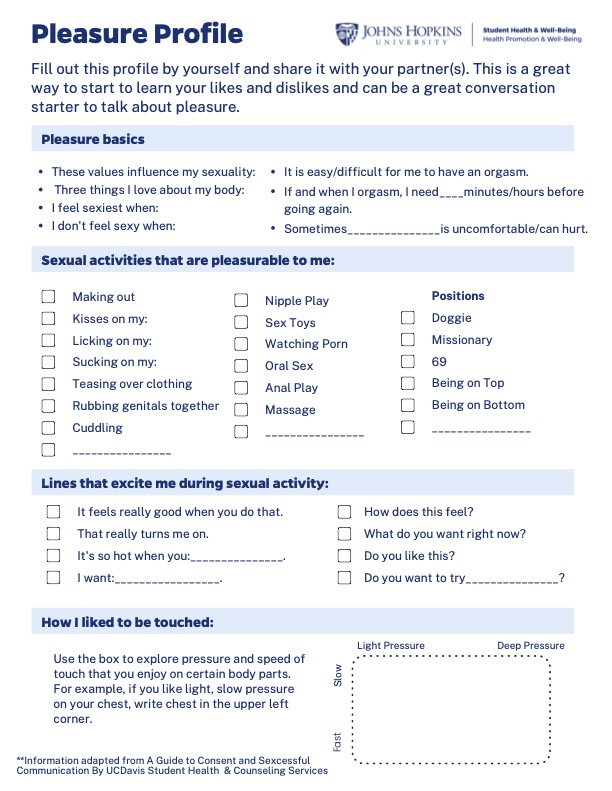

Use (see below) of our pleasure profile worksheet to explore a little about what you like.

Sexual pleasure with others

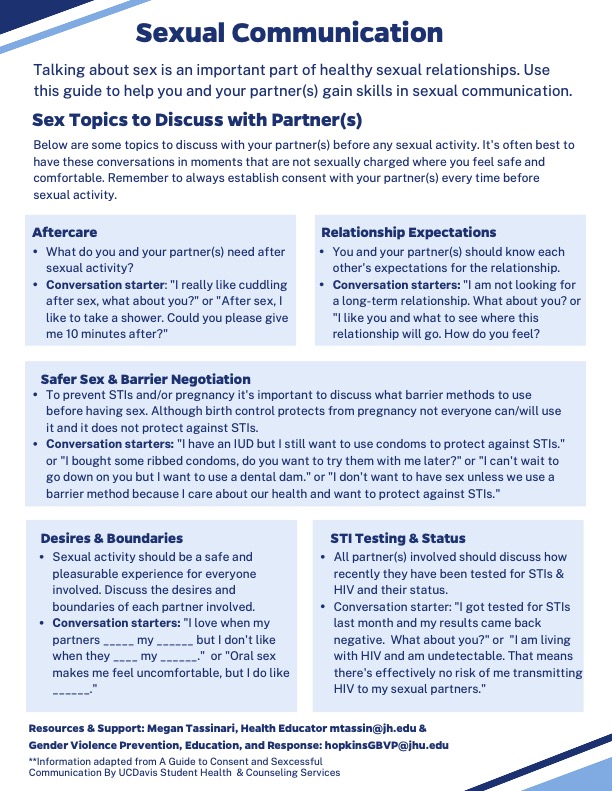

Talk to your partner (or partners) about your boundaries, what you like and don’t like during sex, and how you and your partner/s will communicate about consent during sex. Exploring sex and intimacy with a person or people that you feel safe with and trust can be a part of healing and in reconnecting with your autonomy. Not all people who have experience trauma find healing through sex and sexuality, and that is ok. There are a lot of other ways to experience pleasure that are non-sexual.

Talk about what activities are safe before the encounter begins and how consent will be communicated. Communications around consent can be establishing safe words or actions to halt the sexual activity when needed or talking about things to look out for that might indicate it’s time to slow down or check in.

For example, a safe word can be something like “flamingo” or “grass,” something that is otherwise unlikely to be said as part of the sexual act. A safe action might be something like three taps on a leg. A safe action can be helpful for sex acts that limit speech, but also in the case that a person is unable to speak for any reason.

You can also have conversations about things to look out for that are an indication to check in. For example, a partner might share that that if it seems as if they are not as engaged as they were before or if they are looking away from what is happening, it’s time to slow down and check in. Anyone can struggle with communication during sexual acts, and folks who have experienced sexual trauma might find it especially difficult to communicate during sex (or could be worried about communicating during sex). Because of this, having conversations about what partners like, don’t like, boundaries, and consent before sex can make the interactions feel more safe and more comfortable. Useour pleasure profile worksheet with your partner(s) to explore more.

Dealing with challenges with sex after trauma

Encountering challenges with pleasure or feeling unsafe engaging in sexual activity after trauma is normal. Encountering challenges does not indicate you will never get to where you want to be. Rather, it is indicative that your body is doing what it knows to do to keep you safe (and it’s working, because you are here reading this).

Should frustration around sex and intimacy arise, give yourself patience and grace to move slower (whether you are experimenting with yourself or with others). It can be helpful to approach sexual activity with curiosity and exploration. Notice when your feelings of shame, guilt, frustration come up (without judgement, if you can) and try to reframe or ground yourself in the moment. Allow yourself to take a break or take a few steps back in your sexual engagement such as kissing or cuddling if you feel overwhelmed or uncomfortable.

Managing triggers and flashbacks

Flashbacks and triggers are often thought of as images of the traumatic experience. But they can also be experienced as unpleasant sensations, or a lack of sensation, an experience of disconnection, or an experience of overwhelm. Come up with a plan for these, so it is in place before sex begins.

- Communicate with your partner about your feelings around your triggers or potential flashbacks.

- Remember to establish safe words and actions before sex begins.

- Make aftercare a standard. Aftercare can be anything from cuddling, to taking a nap, to having a snack. The knowledge that aftercare is there can be grounding and can be a safe space to look for.

- When you have a flashback, a part of your brain thinks it is in the past when the trauma happened. Remind yourself that part of your brain that you are in the present moment and that the danger has passed. Another word for this is “grounding.” Here are some ideas for grounding activities.

- Try 5,4,3,2,1. Name 5 things you can see, 4 you can touch, 3 you can hear, 2 you can smell, and 1 you can taste.

- Take deep breaths. Breathe in for a count of 4, hold for a count of 7, and breathe out for a count of 8 (or any variation of that where you breathe out longer than you breathe in).

- Take box breaths. Breathe in for 4, hold for 4, breathe out for 4, hold for 4. Repeat this sequence 4 times.

- Stand up and move your body. Get the adrenaline out. Run on the spot, go for a walk, or do jumping jacks.

- Watch a YouTube video that makes you laugh. Laughter is grounding.

- Play a categories game. Name as many things as you can within a given category (cities, animals, breakfast foods, etc).

- Say the alphabet backwards.

- Show these strategies to your partner and do them together.

If you would like to talk more about sexual pleasure after trauma, please reach out to the Gender-Based Violence Prevention team at [email protected].

You can also schedule an appointment with Mental Health Services.

Additional Reading

- I Spent My Life Consenting to Touch I Didn’t Want by Melissa Febos for The New York Times

- Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good by adrienne maree brown

- Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti

Pleasure Profile Worksheet

This document is available as a printable PDF. You can also click on the following images to enlarge them. For any accessibility issues, please contact [email protected].

Categories

- Environmental (70)

- Financial (69)

- Mental (223)

- Physical (313)

- Professional (185)

- Sexual (85)

- Social (189)

- Spiritual (26)

Archives

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020