Note: this post draws from materials created by Sel J. Hwahng, Ph.D. and David Makonnen, M.Ed., MBA for the UHS Wellness Resiliency & Leadership Workshop Series. Additionally, it was updated on February 15, 2021 to include more detail on what authenticity can cost a person and clarify the difference between an illusion and a delusional belief.

To address imposter syndrome (see below), you have to be authentic. In a Leadership Course based on what is known as the ontological/phenomenological model,1 authenticity is distinguished as being and acting consistent with who you hold yourself out to be for others, and who you hold yourself to be for yourself.2 Authenticity is also regarded as critical to being a leader and to the effective exercise of leadership.

In this workshop series, resiliency is paired with leadership. That is, the development of resiliency involves finding and leveraging your strengths as a leader (versus “fixing” your deficits).

Most leadership training is epistemological, i.e. focused on gaining new knowledge about leadership traits and styles. When people study such new knowledge, they are very rarely able to apply it in real-world situations. Or—if they do apply this knowledge—it is often ineffective because they are emulating someone else’s traits and styles instead of their own natural self-expression.

An alternative to the epistemological approach is an ontological approach. Ontology focuses on who you are being in any situation from one instance to another. By employing ontological-based methods, you are able to discover new openings for action and more freedom in your natural self-expression. Such ontological inquiries have a direct impact on bolstering your resiliency as well as providing openings for contributing to yourself, others, and the world.

In this post, I will define imposter syndrome and explore ontological approaches to addressing authenticity. This can lead to the effective implementation of actions and strategies resulting in greater self-confidence, resiliency, and a higher quality of life.

What is Imposter Syndrome?

Imposter syndrome technically isn’t in the DSM-5, but it’s an extremely common phenomenon.

A recent article defined it as “the notion that some individuals feel as if they ended up in esteemed roles and positions not because of their competencies, but because of some oversight or stroke of luck. Such individuals therefore feel like frauds.” 3

At the heart of imposter syndrome is a deep sense of not belonging, which is why it is often exacerbated by various forms of structural disadvantage such as racism, sexism, heterosexism, and ableism.

Some common imposter syndrome symptoms include:

- Self-doubt (“I think the admissions department must have made a mistake when they let me into this school.”)

- Feelings of inferiority (“I’m the dumbest one here.”)

- Shame (“It’s embarrassing how bad I am at this.”)

- Self-suppression (“If I can somehow hide how terrible I am, maybe no one will realize it.”)

- Inauthentic behavior (“I act like everything is fine in front of others and don’t let anyone know how insecure I really feel.”)

What is Resiliency?

Resiliency is the ability to adapt and grow through adversity, navigate difficult challenges, find a constructive way forward, and to learn and develop helpful attitudes and behaviors.

When resiliency is not present, a person can often experience rigidity, harshness, feelings of isolation, automatic negative thoughts, and imposter fears.

What are Cognitive Distortions?

A lack of resiliency can lead to cognitive distortions, which are incorrect and habitually negative ways of thinking. Common cognitive distortions include:

- All-or-nothing thinking, or assuming that your only outcomes are total success or total failure with no room for error or growth. Also known as black-and-white thinking. (“I hit a flat note while singing; the whole performance was awful.”)

- Catastrophizing, or overestimating the impact of a small setback or mistake. (“This bad grade on this one assignment ruins my hopes of ever getting into graduate school.”)

- Mind reading, or assuming people are focusing on your flaws. (“Everyone’s watching me eating lunch by myself and thinking I’m a loser.”)

- Minimizing, or discounting positive feedback and events. (“The professor said my paper was good but they were just being nice.”)

- Overgeneralization, or making large assumptions based on limited experiences. (“I dropped the class. I’m always such a quitter.”)

- Downward negative spiral (“I did poorly on this exam” becomes “I will flunk out of school” becomes “I will be a huge failure in life.”)

What is Authenticity?

As previously stated, authenticity is being and acting consistent with who you hold yourself out to be for others, and who you hold yourself to be for yourself.

Interestingly, the path to authenticity is being authentic about your inauthenticities.4

Many of us think of ourselves as (more or less) authentic, but each of us in certain situations and in certain ways is consistently inauthentic.5 For example, consider how someone you know may only post “positive” photos of themselves on social media, wearing only specific types of outfits and in specific types of poses, which only shows a narrow aspect of who they really are.

We all want to be admired, even if few of us would openly admit as much. Thus, in situations where we perceive that authenticity will cause a loss of admiration, we will fall short of being straightforward and completely honest.6

For example, consider the student who is externally motivated to ace all their classes because they want the admiration from their parents who can then brag to their friends about their child’s academic achievements. However, this student is actually not really interested in learning the course material but will not be honest to their parents about their lack of interest for fear of losing the admiration from family and friends.

The possibility of looking bad (or disloyal or wrong or stupid or irrational or naïve or silly) can seem so dangerous that sacrificing our authenticity in a given situation seems like a small price to pay. That’s especially true when we don’t necessarily realize we are being inauthentic, or acknowledge that the actual costs (which can include experiencing imposter syndrome) are quite high.

In fact, sacrificing authenticity in the name of admiration, appearing loyal, or “looking good” costs us a lot, such as well-being, vitality, and connection. What may be especially tricky is when we are inauthentic with ourselves. Often, we don’t realize we are being inauthentic with ourselves until we really take time to look at our authenticity. Inauthenticity is fundamental to imposter syndrome so distinguishing authenticity within us can start to loosen the grip of the imposter syndrome.

What are Your Priorities?

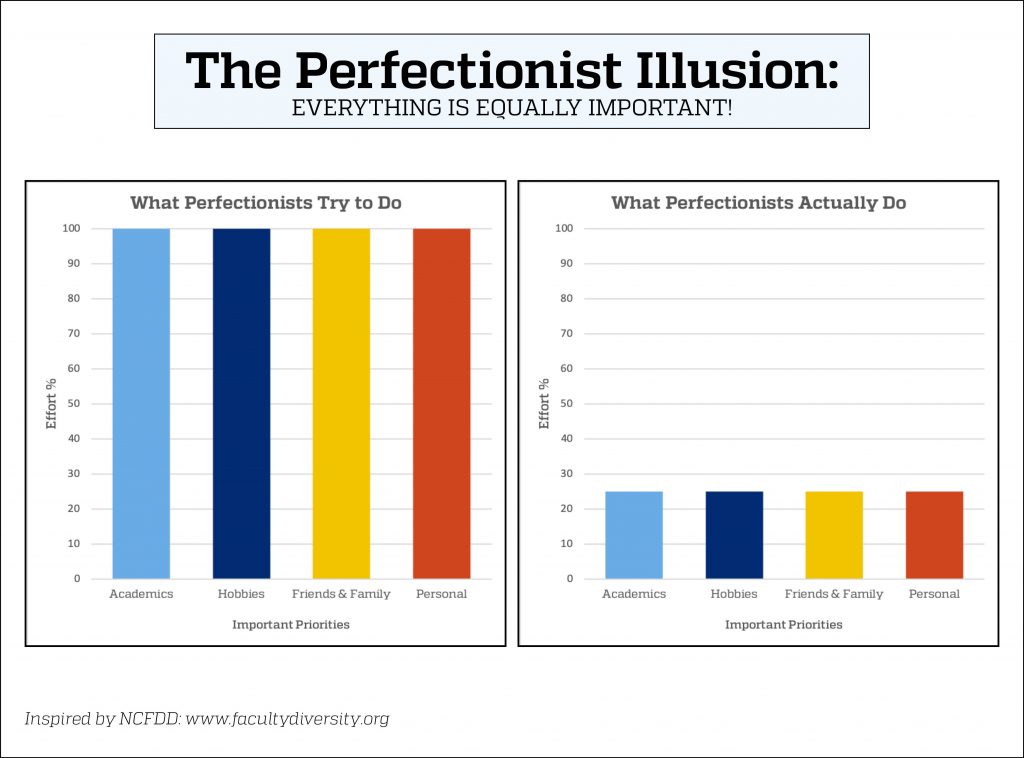

Imposter syndrome often emerges from misplaced priorities, one of them being perfectionism. Perfectionism is the illusion that every aspect of your life is equally important and therefore that every area must be accomplished with the absolute highest standards.

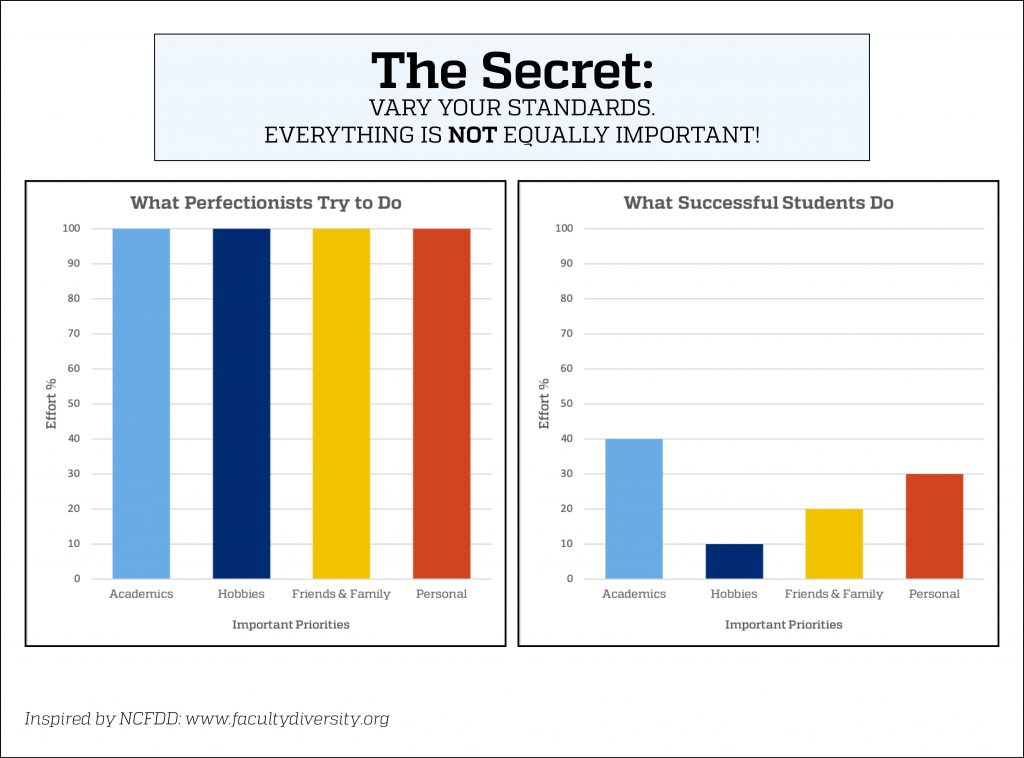

An antidote to perfectionism is to “vary your standards.” Maintain high standards for your top priorities (which should include health and well-being). “Lower your standards” on mid- and low-level priorities. When I say “lower your standards” I do not mean that you fail in those lower-priority areas. There is usually a spectrum between “excelling” and “failing” in any priority area, so for lower-level priorities, consider accomplishing them at a competent but not necessarily a stellar level. This will then free up time and energy for you to really devote your “best” efforts to your top-level priorities.

Realistically, you can only have one or two top priorities in your life (besides health and well-being). It’s important to hierarchize your priorities into top, mid-level, and low-level priorities and then budget your time and energy accordingly. We are much more likely to experience imposter syndrome in our lives when we feel like we don’t belong in our top-level priorities compared to not feeling like we belong in our lower-level priorities.

The idea that lowering your standards is a good thing can sometimes be hard for perfectionists to grasp. But it’s not only a healthy choice; it’s an effective and productive one. Check out these charts.

Please note: the exact proportions in the chart above are not a universal mandate; your personal efforts may be distributed somewhat differently depending on personal circumstances.

I suggest you make “good enough” the standard to which you hold your mid- and low-level priorities. That might look like taking class electives pass/fail, or scaling back your participation in avocations such as volunteering or hobbies, or asking for help. This allows you to focus more fully on your top priorities and create a greater overall quality of life. Here are some examples of ways a person might shift their (sometimes unacknowledged) standards as they pertain to lower priorities.

| Unspoken Standard | Lowered Standard |

| I should say yes to all requests from professors, clubs, and friends and family. | I will say no to non-essential requests. |

| In order to “maximize” my learning, I will do all class assignments by myself. | I will collaborate with others as much as possible when collaboration is allowed. |

| I need to get an A+ in every class. | I can take some classes, especially electives, pass/fail. |

| I should be fluent in tax code and do my taxes by myself. | I will pay someone else to do my taxes. |

| Chart inspired by NCFDD: www.facultydiversity.org | |

Being authentic about yourself and your priorities can contribute to your sense of belonging in your top priority areas, which in turn can diminish imposter syndrome. It can also increase your self-confidence and your self-expression.

***

Clare Lochary, Student Wellness Communications Associate, contributed to the content of this post.

***

Interested in learning more about resiliency and leadership? In addition to the February 1 and March 1 workshops, Dr. Hwahng is also offering an upcoming course on The Performance of Leadership that is open to all Hopkins students. If you are interested in registering for “The Performance of Leadership” course, please contact the JHSPH Registrar’s Office: [email protected].

***

1 Erhard, Werner et al. “Creating Leaders: An Ontological/Phenomenological Model.” The Handbook for Teaching Leadership: Knowing, Doing, and Being, edited by Scott Snook et al., Sage Publishing, 2011, 14.

2 Erhard, Werner et al. “Creating Leaders.”

3 Feenstra, Sanne, et al. “Contextualizing the Imposter ‘Syndrome’.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media S.A., 13 Nov. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7703426/.

4 Erhard, Werner et al. “Course Materials for ‘Being A Leader and the Effective Exercise of Leadership: An Ontological/Phenomenological Model’.” Social Science Research Network, 2020, 749, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1263835.

5 Ibid., 750.

6 Ibid., 751.

Categories

- Environmental (46)

- Financial (49)

- Mental (187)

- Physical (265)

- Professional (160)

- Sexual (68)

- Social (161)

- Spiritual (23)

Archives

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020